Edith Abbott (1876-1957): Social Service Administration

Edith Abbott drove her students hard, and her standards were high. One student commented, "[s]he really is a beautiful woman, but she scares me spitless." Such rigor was basic to Abbott's larger approach.

When she came to Chicago in 1924, most social service agencies operated under private philanthropic or church control. By the time she retired, some thirty years later, government money had transformed the welfare program into a more centralized, allencompassing system, a transformation Abbott believed in absolutely. At the School of Social Service Administration, Abbott trained students to administer the growing social welfare agencies and organizations. As researcher and educator, her primary goal was to aid the professionalization of social welfare administration.

Edith Abbott grew up in Grand Island, Nebraska, in a home where issues of justice, law, women's rights, and state and federal control were considered important. After earning a doctorate from the University of Chicago, Abbott studied economics in London. She returned to Chicago in 1907 to live at Hull House along with her sister Grace Abbott, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Florence Kelley, and Julia Lathrop. This core of female professionals was instrumental in directing many fundamental changes in welfare work during the early decades of the twentieth century.

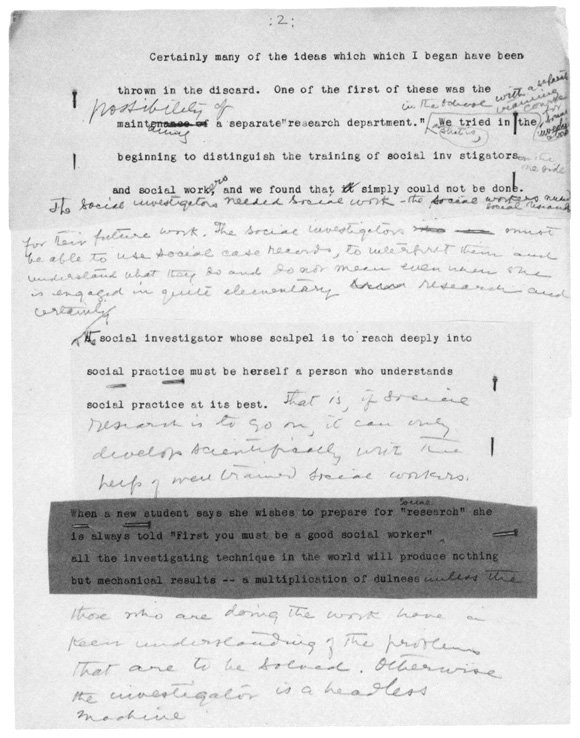

At the University of Chicago, Abbott combined social work with academic research and professional training, a conjunction some considered impractical. Abbott insisted on the juxtaposition because she believed the education of social workers too important to be left to amateurs, however well intentioned. Envisioning modern welfare work as the collaborative effort of specialists trained by practical experience and academic instruction, Abbott, along with her close associate, Sophonisba P. Breckinridge, strongly resisted the suggestion that the new School of Social Service Administration be included in the Department of Sociology. She argued that SSA needed the autonomy granted other professional schools. Approached much like physical ailments, social ills could be diagnosed and treated. Abbott likened the professionally trained social investigator to a surgeon "whose scalpel is to reach deeply."

At Chicago, casework and classwork

linked theory, practical experience, and research. Faculty members closely

supervised students, and grounding in theory was a prerequisite to practical

application. Although accepted today as a basic tenet of social service,

the system was revolutionary in the early decades of this century. Its

legacy is the conviction that comprehensive social welfare programs, properly

designed and administered, represent the best chance to root out society's

ills. This conviction was the centerpiece of Edith Abbott's philosophy.

Although Abbott was committed to rigorous professional training, she retained strong sympathies for the dedicated efforts of settlement house workers. Hull House was her home for many years, and Jane Addams and other residents were close personal friends.

Abbott argued strongly for a close working relationship between social science researchers and social work practitioners. "If social research is to go on," she notes in these remarks, "it can only develop scientifically with the help of well trained social workers."