Science and Medicine

Voorhees Walker Foley & Smith, architects and engineers, predecessor firm of Haines Lundberg Waehler. Perspective drawing by Chester B. Price, ca. 1948. Photograph courtesy of Argonne National Laboratory.

Construction of permanent facilities at the Du Page County site began in 1948, and the new laboratories were in full operation by 1953.

Science in the City

President Harper sought the best men and facilities to support a full complement of scientific programs for the new university. Laboratories, greenhouses, and museums were constructed on the quadrangles, but they were never expected to be large enough to house the activities of University of Chicago scientists. Biologists spent summers at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts; botanists trekked through the lakeshore dunes north and south of Chicago. Bacteriologist Henry Taylor Ricketts traveled to Montana and Mexico to find the source of spotted fever and typhus. James Henry Breasted studied the archaeology of the Near East while Frederick Starr took notes on religious customs and symbols as he made a pilgrimage of the eighty-eight temples of Shikoku in Japan.

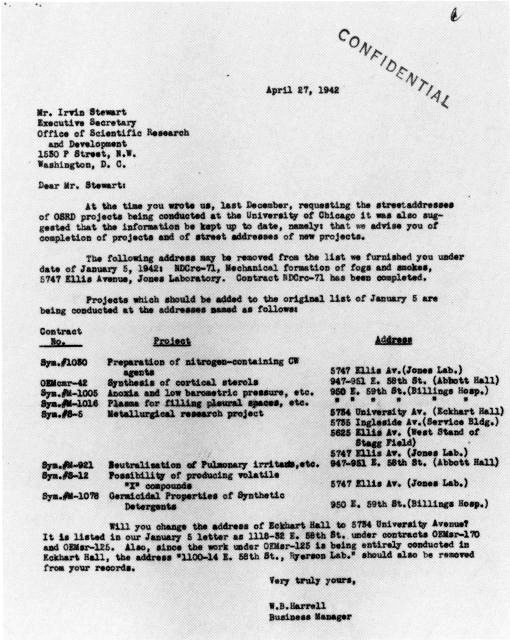

Although the University of Chicago's Department of Physics was well known through the work of Albert A. Michelson, Robert A. Millikan, Arthur Holly Compton, and others, the news which broke after atomic bombs fell on Japan in August 1945 brought the University's scientists to new prominence. There could be no hiding the fact that an international team of physicists and engineers had been assembled on campus early in 1942 for top-secret research; but the announcement that Enrico Fermi and his group had built a nuclear pile and successfully initiated the first self-sustaining nuclear reaction, under the football stands, in the heart of the city, stunned even the faculty members who had eaten lunch every day with the physicists in the Quadrangle Club.

The nuclear pile had been planned for a site in the Cook County Forest Preserve, but a construction workers' strike and severe time constraints forced the group to build it on campus. Although the scientists were convinced their safety precautions were adequate, project director Compton wrote later, "I should have taken the matter to my superior. But that would have been unfair. President Hutchins was in no position to judge the hazards involved. Based on considerations of the University's welfare, the only answer he could have given would have been--no. And this answer would have been wrong."

Work accelerated in October

1942 as problems with equipment and obtaining pure materials were solved

one by one. Orders with "double X priority" for graphite, uranium oxide,

lumber for scaffolding, and a huge square balloon from Goodyear arrived

at the Ellis Avenue laboratory with no questions asked. Youths from

the Back of the Yards neighborhood were recruited to assist physics

students to machine 400 tons of graphite into bricks and press uranium

oxide into 22,000 small spheres.

The Manhattan Project marked a shift in scientific research from privately supported research of individual professors, to massive team projects requiring expensive equipment, sponsored directly by the government. The experience gained in managing huge contracts during the war led to continued cooperation between the government and the University for scientific research and training in subsequent years. Construction soon began on Argonne National Laboratory, built by the government and operated by the University, to continue experiments with new types of nuclear reactors and technology. The University had chosen a farmland site in Du Page County, and soon the sleepy rural villages of Lemont and Downers Grove experienced a boom as scientists, technicians, and other employees sought housing and services close to their work.

While nuclear research under government sponsorship moved to the suburbs, the University sought industry and corporate support to build facilities for basic research on campus. The Enrico Fermi Institute and the James Franck Institute were outgrowths of efforts in the 1950s to expand facilities and spur research in areas which would eventually be of use to industry and business. Medical uses of radioactive isotopes were explored in the Argonne Cancer Research Hospital on Ellis Avenue. With funding from NASA, the University built the Laboratory for Astrophysics and Space Research, which provided facilities for University research connected to NASA's space flights.

When government support declined in the 1980s, the University sought better means to connect the long-term goals of its research programs with the needs of businesses and industries which could benefit from its discoveries. Closer relationships needed to be developed to increase commercial dissemination of products and processes derived from laboratory investigations. In 1986 ARCH was created-the Argonne National Laboratory-University of Chicago Development Corporation-to assist in moving scientific discoveries from research laboratories to the marketplace. ARCH coordinated the development of industrial applications from scientific research and, with support from the Graduate School of Business, assisted with venture capital, marketing strategies, and management for commercial spin-offs.

Within weeks of the end of the war, President Hutchins announced plans for new institutes for scientific research to be built on campus. The buildings were constructed across the street from the old Stagg Field stands where "CF-1," the first atomic pile, had been built. Photograph by Rus Arnold.

While nuclear research under government sponsorship moved to the suburbs, the University sought industry and corporate support to build facilities for basic research on campus. The Enrico Fermi Institute and the James Franck Institute were outgrowths of efforts in the 1950s to expand facilities and spur research in areas which would eventually be of use to industry and business. Medical uses of radioactive isotopes were explored in the Argonne Cancer Research Hospital on Ellis Avenue. With funding from NASA, the University built the Laboratory for Astrophysics and Space Research, which provided facilities for University research connected to NASA's space flights.

When government support declined in the 1980s, the University sought better means to connect the long-term goals of its research programs with the needs of businesses and industries which could benefit from its discoveries. Closer relationships needed to be developed to increase commercial dissemination of products and processes derived from laboratory investigations. In 1986 ARCH was created-the Argonne National Laboratory-University of Chicago Development Corporation-to assist in moving scientific discoveries from research laboratories to the marketplace. ARCH coordinated the development of industrial applications from scientific research and, with support from the Graduate School of Business, assisted with venture capital, marketing strategies, and management for commercial spin-offs.

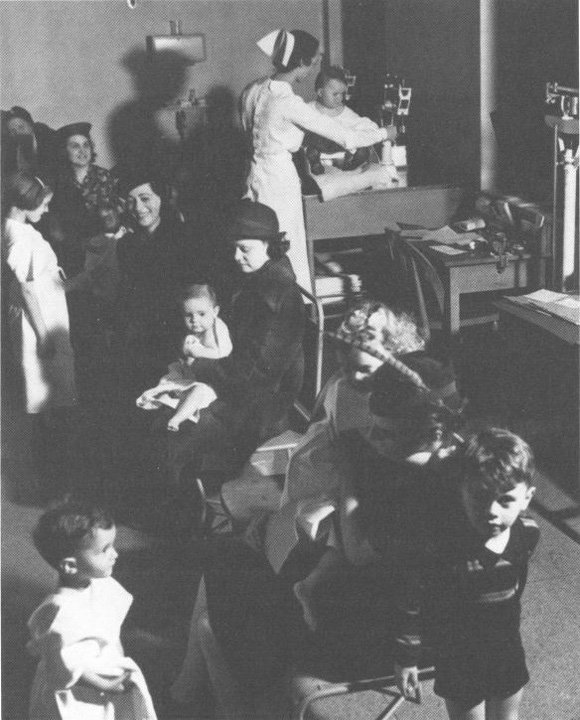

The Bobs Roberts hospital treated patients for the Department of Pediatrics until its work was taken over by the Wyler Children's Hospital, which opened in 1967.