Robert Maynard Hutchins (1899-1977)

Chancellor 1945-1951

William Rainey Harper brought the University of Chicago into being, giving it form and life and mission. But it is the legacy of Robert Maynard Hutchins which is still avidly discussed and debated. Although Hutchins brought his own ideas and innovations with him, he came to embody the spirit of the University in a way no one else has since Harper. Hutchins was immediately compared with Harper-young, energetic, brilliant, charismatic. Unlike Harper, though, he was an iconoclast who ridiculed empty rhetoric, shabby reasoning, and institutions which did not fulfill their promise. He could say, with a straight face:

I do not need to tell you what the public thinks about universities. You know as well as I, and you know as well as I that the public is wrong. The fact that popular misconceptions of the nature and purpose of universities originate in the fantastic misconduct of the universities themselves is not consoling.

Late in life Hutchins mused about his years in Chicago, "Our idea there was to start a big argument about higher education and keep it alive." The son of a preacher, he portrayed himself as a prophet without honor in his own country, the lone voice of reason in a world of mediocrity. He often quoted a line from Walt Whitman, and once suggested it as a motto for the University of Chicago: "Solitary, singing in the west, I strike up for a new world." Claiming that "thinking is an arduous and painful process, and thinking about education is particularly disagreeable," Hutchins focused on the highest abstractions-morals, values, the intellect, the "University of Utopia," the "great conversation," and above all the study of metaphysics-while others, he claimed, preferred to deal with "academic housekeeping." In fact he inspired a loyal cadre of admirers and fans who spread his gospel across the land.

Hutchins was educated at Oberlin and Yale, and his speaking abilities were already recognized when he addressed the annual alumni dinner during his senior year. After teaching for a year and a half at a private school in Lake Placid, New York, Hutchins was invited by Yale president James R. Angell to return as secretary of the university. While working full-time, Hutchins completed law school, and upon receiving his degree in 1925 was appointed a lecturer.

Two years later he was made

a full professor, and he soon received the additional responsibilities

of acting dean. In 1928 he was appointed Dean of the Law School. While

there he helped organize the Institute of Human Relations and promoted

the use of modern psychological studies to evaluate rules of evidence.

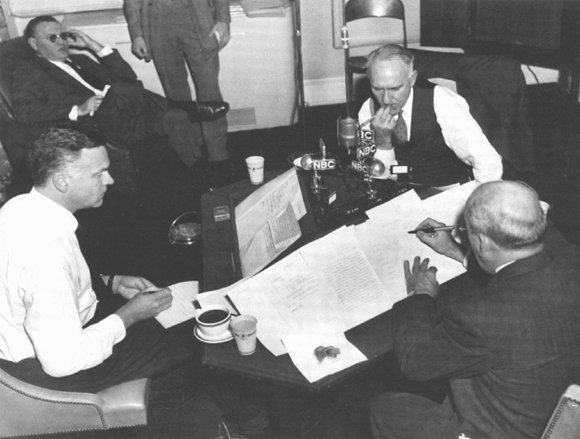

Robert M. Hutchins, Floyd W. Reeves, and John T. McCloy discuss: "Should We Have Military Training in Peacetime?" November 26, 1944.

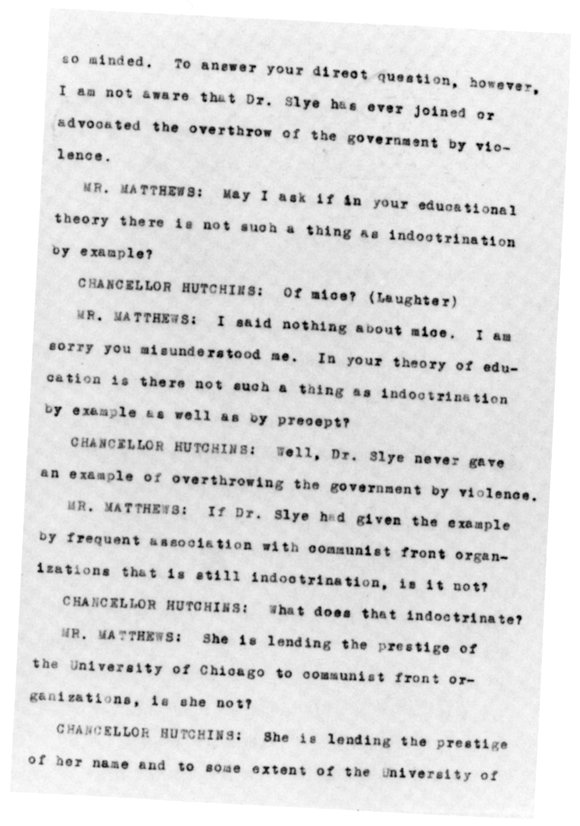

Hutchins was grilled concerning suspicious political activities of faculty members, including Maud Slye, an emeritus professor of pathology who had spent most of her career in the laboratory studying the heredity of cancer in mice.

Hutchins concluded that the legal rules were often based on faulty assumptions about human behavior, but also that psychologists had never studied the question in a useful way.

Compiling a list of candidates to succeed Max Mason after his resignation in 1928, the University of Chicago presidential search committee included Hutchins's name among other college presidents and deans. Although they sought someone young, between 35 and 50, Hutchins, then only 29, was soon dropped from the list. His name resurfaced as the winnowing process continued. Although Hutchins's talents were clear, some wondered if his experience and maturity were sufficient. After a long interview session, the committee was persuaded it was worth the gamble, and Hutchins was elected president in April 1929.

Hutchins gave 64 public addresses in his first year at the University, establishing a public presence and identity seldom equalled by a university president before or since. Appearing regularly on the radio, in the pages of popular magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post, as well as at convocations and alumni meetings, Hutchins personally represented in the popular mind the ideals of higher education as well as the particular programs of the University of Chicago

Hutchins arrived during a peak of activity on the University campus. Buildings begun under Burton and Mason were being completed, and departments were moving into new facilities. The new, immense University Chapel was finished only months before Hutchins's inauguration. Years of planning for a new undergraduate program were culminating in a "New Plan" which was nearly ready for unveiling. Hutchins endorsed the changes in the College and adopted them into his personal campaign to change American education.

The Chicago College eliminated

grades and course requirements, replacing these with broad-based general

education classes and a series of comprehensive exams. Hutchins advocated

the relocation of the BA degree to the sophomore year of college, focusing

the bachelor's degree on general or liberal education, and leaving specialization

for the master's. This plan had been put forth by President Judson fifteen

years earlier, and indeed harked back to Harper's plan for junior and

senior colleges. Hutchins also became known for his emphasis on the "great

books," through the evening courses he co-taught with Mortimer Adler and

his support of the adult groups which mushroomed throughout the country

in the 1940s, although the University never actually adopted the great

books program into its curriculum.

The purpose of the

university is nothing less than to procure a moral, intellectual, and

spiritual revolution throughout the world.

—Robert Maynard Hutchins

While Hutchins was best known for his statements on undergraduate education, one of his most enduring reforms at the University was the organization of the graduate departments into the four academic divisions of the biological sciences, humanities, physical sciences, and social sciences, with a separate College which unified all undergraduate work under one dean.

The one thing which drew more attention than any other, of course, was his elimination of varsity football. Hutchins heaped scorn upon schools which received more press coverage for their sports teams than for their educational programs, and a run of disastrous seasons gave him the trustee support he needed to drop football in 1939. The decision was hailed by many, but few other schools followed Chicago's lead.

The Hutchins administration

spanned both the Great Depression and World War II, trying times for higher

education and the nation as a whole. Funds raised in the 1920s and continuing

support from the Rockefeller Foundation gave the University a cushion

many other institutions did not have, especially in the early years of

the depression. When war threatened, Hutchins opposed it, but after the

attack on Pearl Harbor he offered the government the resources of the

University.

Millions of dollars in government contracts poured in to support specialized training programs for military personnel in languages, radio technology, and meteorology, and for research vital to the war effort. The Manhattan Project which developed the atomic bomb was only one of many projects operating on the University campus during the war years.

By 1944 Hutchins again began preaching for peace, and the atomic bomb made his message all the more urgent. After the war he joined in the efforts of the Committee to Frame a World Constitution to push for a world government, yet another appearance of Hutchins's resilient idealism.

Hutchins was a strong advocate of academic freedom, and as always refused to compromise his principles. Faced with charges in 1935 by drugstore magnate Charles Walgreen that his niece had been indoctrinated with communist ideas at the University, Hutchins stood behind his faculty and their right to teach and believe as they wished, insisting that communism could not withstand the scrutiny of public analysis and debate. He later became friends with Walgreen and convinced him to fund a series of lectures on democracy. When the University faced charges of aiding and abetting communism again in 1949, Hutchins steadfastly refused to capitulate to red-baiters who attacked faculty members.

Hutchins resigned in 1951 to become an associate director of the recently-created Ford Foundation. In 1954 he took over chairmanship of the Foundation's Fund for the Republic, which sponsored research on civil rights issues including blacklisting of Hollywood actors and freedom of the press. After many years of planning, in 1959 he was able to initiate the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. Located on an estate near Santa Barbara, California, the Center offered daily programs where senior residents could meet with invited guests in small groups to study position papers and engage in informal discussions. In its broad scope and open agenda, the Center embodied the hopes and ideals to which Hutchins had dedicated his career.