Ernest DeWitt Burton (1856-1925)

Professor and Head of the Department of New Testament and Early Christian Literature 1892-1925

Director of the University Libraries 1910-1925

Acting President 1923

President 1923-1925

Ernest DeWitt Burton was born six months before William Rainey Harper, and their careers paralleled each other in several ways. They met while Harper was teaching Old Testament Hebrew at Yale and Burton was teaching New Testament Greek nearby at the Baptist seminary in Newton Center, Massachusetts. Sharing respect for both conservative values and the new techniques of "higher criticism" in Biblical scholarship, it seemed natural that Burton should join Harper's faculty when the University of Chicago opened.

Son of a Baptist preacher, Burton grew up in Ohio, Michigan, and Iowa, and attended college at Denison University, graduating in 1876. After teaching for several years he decided to enter Rochester Theological Seminary, where his brother served on the faculty. Uncertain about his career goals, he thought first of a foreign mission, but his health would not permit it. He taught Greek for a year while his professor was on sabbatical, then sought ordination and a position in the ministry. Before he located a parish he was offered a professorship at Newton Theological Institution.

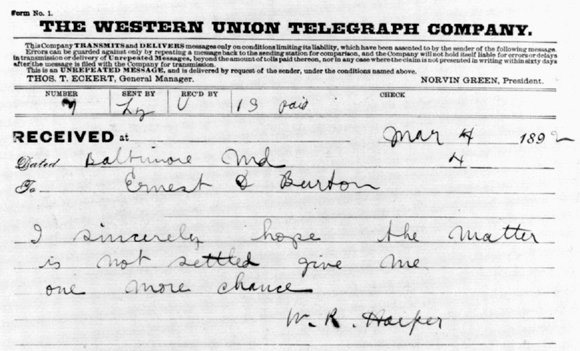

Harper first approached Burton in the spring of 1891 about coming to Chicago. Burton was reluctant to leave a very good position at Newton and wanted specific commitments about responsibilities and salary before agreeing to move. Harper would not relent, and Burton finally accepted on March 24.

Although Burton knew little about athletics before becoming president, he soon realized the importance of football to the University's image. Shortly before this game, plans were announced to build a new football stadium with double the existing seating capacity of 32,000.

If I read the signs of the times aright, the battle of Christianity in this country for the next quarter century is to be waged somewhat more fiercely in the Mississippi Valley than on the New England coast. find in the Mississippi Valley, perhaps no place will be so nearly the very heart and center of the conflict as the city of Chicago . . . . I have always advised on the principle that, other things being equal, the place that was nearest the edge of battle furnished largest evidence of being the one to which Providence called.

Burton was a prodigious writer, publishing serious biblical studies as well as popular books and manuals for church and school use. His exhaustive lexicographical analysis of three Greek roots, Spirit, Soul, and Flesh, was merely the background research he felt was necessary before he could finish his real project, a commentary on the epistle to the Galatians.

In 1908, Burton was chosen to head a commission to investigate educational, social, and religious conditions in the Far East. John D. Rockefeller had received repeated requests from mission boards, the international YMCA, and other bodies to assist in their work in China and other countries. Rockefeller agreed to fund a study of the current situation, to be sponsored by the University of Chicago. In joining the commission, Burton fulfilled his longheld wish of going to China and assisting foreign missions.

Departmental libraries were scattered all over campus, and each had its own collection policies and cataloguing system. Burton plunged into reorganization, considering it a pleasant diversion from his scholarly work. Some libraries were consolidated in the new building, while information on all holdings was brought together for the first time in a central catalog. Burton hired J. C. M. Hanson from the Library of Congress, secured University approval of the Library of Congress classification system, and supervised the creation of a single integrated catalog for the entire book collection.

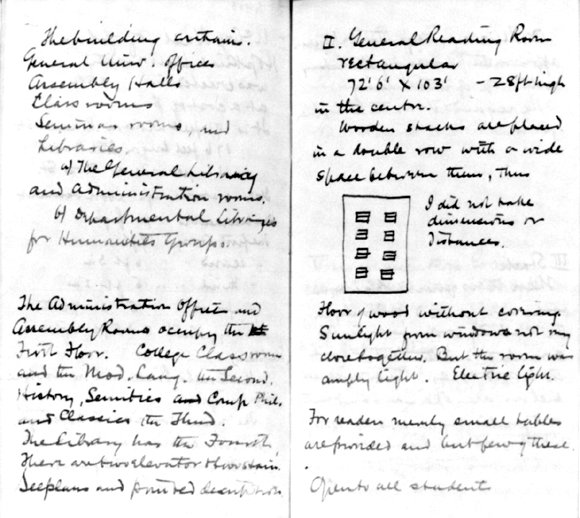

Burton visited libraries and other buildings on many campuses while making plans for a new library at the University of Chicago.

Built on the site of the old Rush Medical College building, Rawson Laboratory was intended to be the center for post-graduate medical research of the University's medical school.

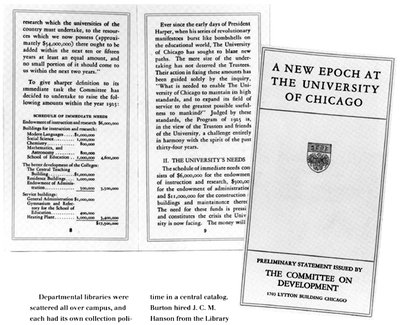

This small brochure laid out the Committee on Development's appeal for funds to construct new buildings, raise faculty salaries, and accommodate a student body which had grown to 13,359 students.

I long ago decided that anything that could be finished in my lifetime was necessarily too small an affair to engross my full interest.

-Ernest DeWitt Burton

Criticized by some for his modern approach to biblical scholarship, Burton nonetheless received strong support within his denomination and served it in many capacities. He was chairman of the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society, helped to found the Northern Baptist Convention, served on its Board of Education for many years, and in 1918 headed a commission to promote unity and coordination among the various missionary and educational efforts of the Baptists. At the same time, he was a teacher and superintendent in the Sunday School of the Hyde Park Baptist Church.

Burton planned to spend his last years completing several lengthy research projects, but his life took another abrupt turn in 1923 when he was asked to succeed Harry Pratt Judson as president of the University. Already 67, Burton asked the Board what it expected from him as acting president. After Board Chairman Martin A. Ryerson told him the word should be "active" rather that "acting," Harold Swift recalled that while Burton "made no answer at that time, his face lighted up and his eyes kindled, probably at the thought of some of his cherished dreams." Although Burton was president for only two years, he sparked a period of expansion and change that was rivaled only by the days of the University's founding.

Burton embarked on an ambitious development campaign to raise millions of dollars for endowment and an extensive building program. Plans for a new medical school and hospital which had been stalled by the war were revived. Burton called upon Franklin McLean, who had overseen the construction and establishment of Peking Union Medical College, to use his experience in China to develop a medical program in Chicago. Burton also initiated comprehensive studies of the colleges and graduate programs, with an eye to improving both their curriculum and administration.

Although he had been plagued with bouts of ill health throughout his life, the presidency seemed to bring Burton new stores of vigor. However, with little warning, an intestinal cancer was found in April 1925, and within a month he was dead. Burton did not live to see his plans completed, but he set the stage for an important new period of growth and experimentation at the University.