London Defiant, The Genius of Place, and Genius London

London Defiant – Nicholas Bellinson

As the Reformation polarized Europe along religious lines, England remained uncomfortably in the middle, wary of and alienated from both the Roman Church and continental Protestantisms. London, as the political and religious capital of England, was on guard against dangerous influences – mostly “Popish” – at home and abroad. The documents in this case illustrate Londoners’ responses to felt tensions with Luther, with the Pope, with Rome, with neighboring France, and with London’s even closer neighbors, the denizens of the English countryside. A formative moment in the process of English isolation appears in Henry VIII’s withering response to a 1525 letter from Luther, containing material which Henry would later use to refute his own earlier Catholic writings and to define his own position as the head of the new Church of England. The three pamphlets in this case arose in the context of the so-called “Popish Plot” (1678-c.1685). Titus Oates – a born Baptist and former Anglican preacher who had converted to Catholicism, been expelled from Catholic seminaries in Spain and France, and stolen sacramental wafers which he used to seal his letters – fabricated a Jesuit plot to assassinate King Charles II and place his Catholic brother James on the throne. The ensuing hysteria claimed around thirty-five Catholic lives; even after Oates’s deception was exposed, Catholic conspiracy theories abounded. These diverse creative reactions to the exaggerated fear of Catholic insurrection in late seventeenth-century London show how religious tension itself became a tool for the exploration of London’s other tensions, geographic, economic, and political.

Elkanah Settle (1648-1724)

[London: s.n., 1679]

Rare Books Collection

In 1679, a burlesque of Catholic villains took place at London’s western gate. It included a priest “giving Pardons very Plentifully to all those that should Murder Protestants, and Proclaiming it Meritorious”; the Pope’s doctor “with Jesuites Powder in one hand, and an Urinal in the other”; and the Pope himself, in effigy, “caressed” by the devil. A “cardinal” and the “people” sang a song in parts (seen here), and the Pope was “Toppled from all his Grandeur into the Impartial Flames”. This pamphleteer balances the irreverence of this effigy-burning against the actual burning of Protestants by the Inquisition, and also against the Pope’s treacheries (i.e. the Popish Plot)

Roger L’Estrange (1616-1704)

[S.l.: s.n., 1680?]

Rare Books Collection

Even after the Popish Plot was discredited, anti-Catholic sentiment threatened to erupt in violence. Here “Goodman Country” vindicates English countryfolk from urban suspicions of Popery. Urging moderation of the “fiery zeal of some that are call’d Protestants”, he warns that a “Holy War” against rural “Catholics” –probably in fact Anabaptists, Presbyterians, and Independents–would be bloodier than the Civil War of the 1640s, from which the countryside was still recovering. Country insists that “stratagems of Jesuited Polititians” exacerbated the conflicts of 1640 and 1641, and that the same “Machiavillian Brains” were now working to divide English Protestants who in reality stood united against Rome.

[London?: s.n., 1680?]

Rare Books Collection

In the 1600s, the papacy struggled to maintain meaningful power, even in Catholic countries. In France, Louis XIV increasingly asserted royal control over the clergy. In response, Pope Innocent XI issued briefs reminding Louis that the Catholic religion was the basis for worldly power. Although England had long since withdrawn from the Roman Church, here “Anglicus” (“Englishman”) writes that the subject “requires our Answer, and not [Louis’s]”. Anglicus rejects the Pope’s argument; he also implies that, the Pope would not have resorted to the “Treachery” of the Popish Plot if he felt truly assured of Catholic France’s eventual conquest of England.

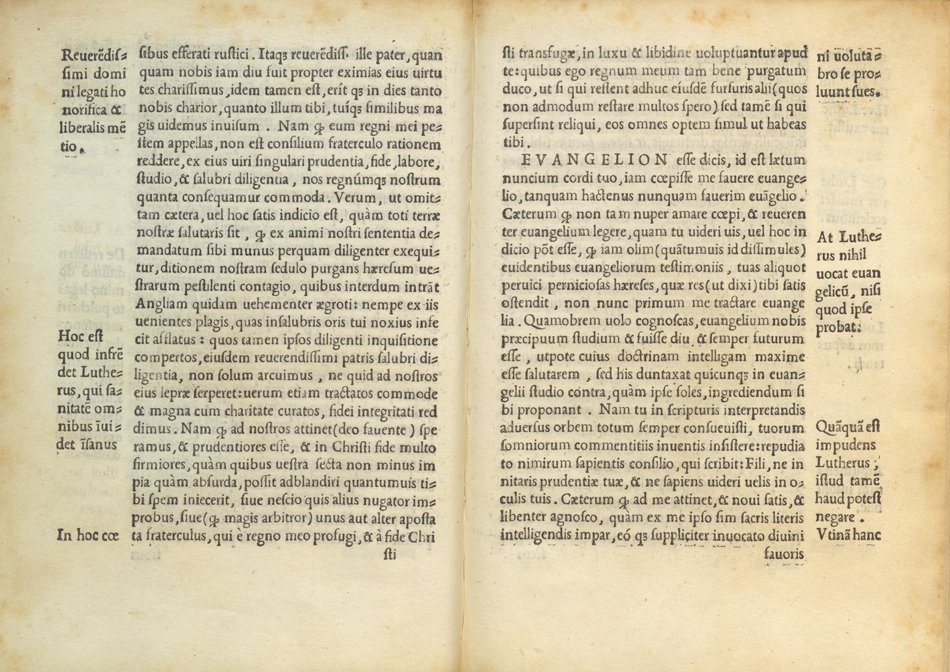

[S.l.: s.n., 1543?]

Rare Books Collection

Henry VIII’s Defence of the Seven Sacraments (1521) refuted Martin Luther’s criticisms of the Roman Church. Luther dismissed the Defence, denying that Henry was the author. In 1525, Luther apologized to Henry and tried to reconcile their doctrinal disagreements. Henry’s response, on display here, was an excoriation of Luther. Perhaps in retaliation, when Henry broke from the Church in 1534 to divorce Catherine of Aragon, Luther sided with the Queen. Nevertheless, as head of the new Church of England, Henry cited Luther’s lines challenging his authorship of the Defence as evidence that he had never authored such a pro-Catholic document in the first place.

The Genius of Place – Caryn O'Connel & Nicholas Bellinson

Michael Drayton (1563-1631) wrote epic, pastoral, satirical, and historical poetry, plays in verse, also religious poetry, some of which was banned and destroyed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Drayton was a court favorite of Queen Elizabeth, but rejected by her successor James I. In 1610 he published the first section of his massive 15,000 line Poly-Olbion, whose verses survey the topography, history, natural history, and legends of Britain’s many counties. While Drayton invoked a Muse to inform his work (“Thou Genius of the place”), he published his poem with annotations by a scholar who cast doubt on the suitability of genii loci to scholarly enterprises. As an artifact, Poly-Olbion embodies early seventeenth-century England’s tensions concerning the proper sources of knowledge. It also captures tensions about the sites it describes, departing from contemporary pastoral conventions by praising, not just the spirit of rural locales, but also the genius of cities, above all “Great London.” Drayton celebrated London as a great source of wealth to England, though he deplored the squandering of this wealth by idle gentry,

...whose disproportion drawes

The publique wealth so drie, and only is the cause

Our gold goes out so fast, for foolish foraine things,

Which upstart Gentry still into our Country brings.

Drayton condemned England’s dependence on foreign luxuries popular with the gentry, like silk and tobacco (“trash… of which we nere had need”), to the neglect of domestic products (“our Tinne, our Leather, Corne, and Wooll”). This polemical digression synthesizes tensions between urban and rural, public and private, foreign and domestic.

The Genius of London – Caryn O’Connell

Where does new knowledge come from? Many seventeenth-century Londoners would answer: “London.” In his 1603 Survey of London, John Stow declared that “learninges of all sortes . . . doe flourish onely in peopled towns.” For Francis Bacon, the “learnings” flourishing most were the “vulgar” mechanical arts, yet, against the grain, Bacon argued that these arts were a source of knowledge of causes, i.e. theoretical science. Bacon’s affirmation of the intellectual fertility of urban spaces fostered a groundswell of activity in London, central to the emergence of experimental science. This in turn generated vehement tensions about knowledge’s sites and sources. Some disagreements concerned social distinction, contrasting the knowledge generated by vulgar and gentle classes, and places. Other tensions relate to two classical terms, both related to the modern concept of genius: ingenium and genius loci. Ingenium held a range of meanings in the Renaissance, from ingenuity, to innate mental ability, learned skill, mastery of an art, or an “ingenious” made thing, such as a clever instrument. Genius loci, or “genius of the place,” referred to a spirit which watched over and characterized a locale. For poets, the genius of a place could double as a Muse stoking imaginative thought, whose inspiration could generate valid knowledge about the world. Volatile forms of ingenium demonstrated in these seventeenth-century artifacts show how practitioners framed knowledge production in terms of the material and immaterial, the place-bound and placeless, offering competing and complementary accounts of what made London so “flourishing” and so genius.

Robert Hooke (1635–1703)

London: Printed by Jo. Martyn and Ja. Allestry, 1665

Rare Books Collection

This book encourages the comparison of two of ingenium’s poles: the “wits of men” and the “mysterie of vintners.” The word “mysterie” meant, among other things, a craftman’s expert knowledge and skill. Charleton glosses “wit”—the most common English translation of ingenium—as “the natural capacity of understanding.” The London physician intended his discourses as practical guides. The first discourse was a guide to the transformation of “wits” understood as mental faculties and dispositions— i.e., a “subtle” judgement or a “tardy” imagination; the second takes up the technology of winemaking. The joint publication of these titles and their parallel construction encourages readers to compare their subjects.

Margaret Cavendish (1624?-1674)

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, 1668. 2nd edition

Rare Books Collection

The first Englishwoman to publish theoretical science and science fiction, Margaret Cavendish was deeply anti-empiricist. Although interested in the London experimentalists, she was critical of them. Her position has been seen as a Duchess’s disavowal of the knowledge production of mechanics. This account, however, overlooks her concern with scientific method. For Cavendish, the place of new knowledge production was the intellect, not the laboratory; the fruits of Cavendish’s wit—like her fiction’s “ingenious Spirit”—are superior to physical discoveries. She singles out sense-based, “ingenious” microscopy as deceiving.

Joseph Moxon (1627-1700)

London: Printed for Joseph Moxon, 1677

Rare Books Collection

This book described the arts of blacksmithing, joinery, carpentry, and turning. Like Micrographia, it represents knowledge as arising from local circumstances, such as the 1666 fire of London. It also uses “ingenuity,” mainly to describe London “workmen,” their creations, and Hooke. Yet Moxon differs from Hooke, as these pages show. For Hooke, knowledge was limited when “imprison’d” in a craftsman’s body: a technique or an understanding of the properties of wood or heat remained unshared. For Moxon, one had to practice an art with one’s body in order to grasp it.

Walter Charleton (1620–1707)

London: Printed by R. W. for William Whitwood, 1659

Rare Books Collection

This book encourages the comparison of two of ingenium’s poles: the “wits of men” and the “mysterie of vintners.” The word “mysterie” meant, among other things, a craftman’s expert knowledge and skill. Charleton glosses “wit”—the most common English translation of ingenium—as “the natural capacity of understanding.” The London physician intended his discourses as practical guides. The first discourse was a guide to the transformation of “wits” understood as mental faculties and dispositions— i.e., a “subtle” judgement or a “tardy” imagination; the second takes up the technology of winemaking. The joint publication of these titles and their parallel construction encourages readers to compare their subjects.