A Jewish Humanist Between Cities and Between Worlds

Tali Winkler

Elia Levita (or Elye Bokher, or Eliyahu ben Asher HaLevi Ashkenazi; 1469-1549), was a Jewish grammarian, lexicographer, and poet active in 16th century Italy, and a pioneer of Renaissance Hebrew scholarship. Born in Neustadt, near Nuremberg, he worked in Venice, Padua, Rome, and Isny, Germany. Levita lived a life on the margins. Like many humanists, he was dependent upon the good will of his patrons, but also upon the limits of his Christian hosts’ tolerance of a Jewish presence. His relationship with Jewish community was also strained, due to his attraction to the Christian world, his opposition to certain rabbinical dogmas, and his involvement in humanism, which some rabbis saw as a threat to traditional Judaism.

Levita greatly influenced Christian Hebrew scholarship. He taught Hebrew to numerous humanists, including his patron Cardinal Egidio da Viterbo in Rome. Levita’s Hebrew grammar books were staples of Hebrew studies in Germany for decades. He drew criticism from his Jewish peers for his Biblical scholarship, which argued that Biblical vowels and accents had originated in the 7th-11th centuries, rather than with Moses at Sinai or Ezra the Scribe. Levita also contributed to Yiddish literature, composing Yiddish chivalric poetry, producing the first printed Yiddish-language lexicon, and translating books of the Hebrew Bible into Yiddish. His translation of Psalms was the first Yiddish book printed in Italy.

Levita’s work defies easy categorization and spans genres. Historians of early Yiddish and of Christian biblical scholarship both claim him as a key figure in their fields, while practically ignoring his contributions to the other. This fact is itself a testament to his skill at bridging multiple worlds, and navigating the social tensions which divided Renaissance Europe.

Levita produced commentaries on the works of brothers Moses and David Kimhi, important medieval Jewish grammarians and biblical commentators. The volume on the left is Levita’s commentary on a work by Moses, and is in both Latin and Hebrew. It contains extensive marginal notes, primarily in Latin. The volume on the right is an edition of one of David’s grammatical works, with glosses by Levita, who is called “the expert grammarian” on the title page. This work was issued in separate editions for Jews and Christians, with the date being given in the anno mundi of the Hebrew calendar and anno domini of the Christian calendar, respectively. This copy bears an owner’s inscription in Hebrew by a Meir Wagner of Altona, who purchased it “in honor of my Rock and my Creator” in the year 1800, as well as some marginal notes in Latin.

Levita wrote two works on the history of masoretic notations. These notations consist of both diacritical marks, used to represent vowel sounds or distinguish between alternative pronunciations of Hebrew letters, and cantillation marks, which act as punctuation and guide the ritual chanting of the biblical text. Levita argued that the traditional notations were standardized in the seventh through eleventh centuries, rather than received by Moses or Ezra the Scribe. His work made a lasting contribution to the development of textual criticism in biblical studies. Here we see editions of these two works printed more than two centuries apart.

Elijah Levita (ca. 1468-1549)

Venice: D. Bomberg, 1538

Rare Books Collection

The Tov Ta‘am is entirely in Hebrew. Given the flourishing study of the Hebrew bible by Christian scholars in the 16th century, it likely had both a Christian and Jewish audience. Interestingly, this copy of the work is bound with two ethical treatises written by Rabbi Jonah Gerondi (d. 1264). The work was censored in 1617, and the ethical treatises bear additional censors’ marks. Such censorship of Hebrew books by the Catholic Church was common in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Elijah Levita (ca. 1468-1549)

Halle im Magdeburgischen : Carl Hermann Hemmerde, 1772

Rare Books Collection, Berlin Collection

This is an 18th-century translation of the Massoreth hammassoreth into German by Christian Gottlob Meyer, a Jewish convert to Christianity. The publisher, Johann Salomo Semler dedicated this edition to Moses Mendelssohn, the famous German Jewish philosopher of the Enlightenment. Ironically, Mendelssohn rejected Levita’s claims and actually defended the traditional Jewish view that the masoretic tradition dated back to Ezra, or even Moses.

Bazily’ah: Ludvig Kinig, [1618]

Rare Books Collection, Hengstenberg Collection

The first Rabbinic Bible—containing the Biblical text in Hebrew, an Aramaic translation, and at least one commentary on each biblical book—was published in Venice in 1517 by Daniel Bomberg. Levita helped edit the third Rabbinic Bible (1546), and even wrote a poem upon its completion celebrating the publication of such a magnificent book. While acknowledging that Bomberg was not Jewish, he praises him as “righteous among the nations” and “circumcised of the heart.” This volume is the sixth Rabbinic Bible, published in Basel in 1618 by Johann Buxtorf. The text is almost identical to the edition which Levita edited.

Bazily’ah: Ludvig Kinig, [1618]

Rare Books Collection, Hengstenberg Collection

The celebratory poem written by Levita for the third edition is reproduced in this volume. The original publication details, such as the city where it was printed, are left in the poem so as not to interrupt the rhyme scheme. The publication details for this edition are included in parentheses.

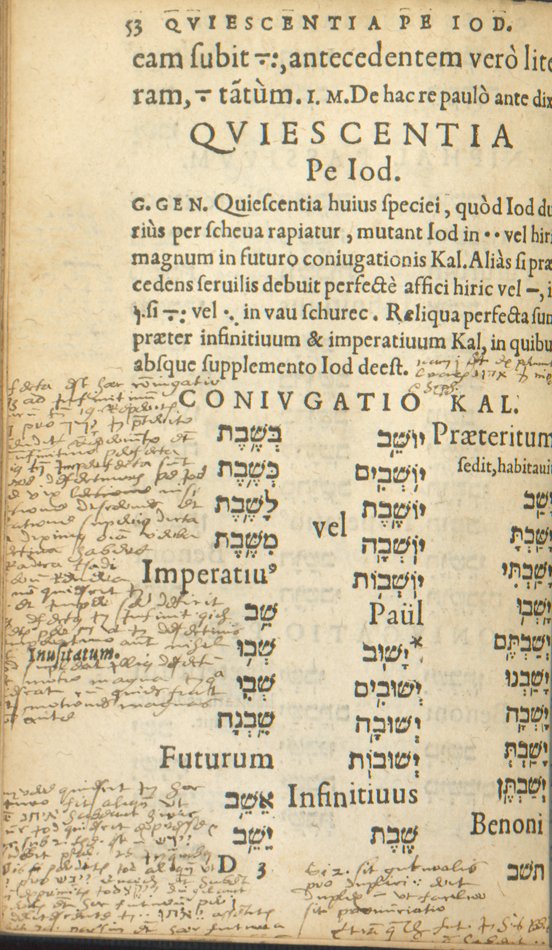

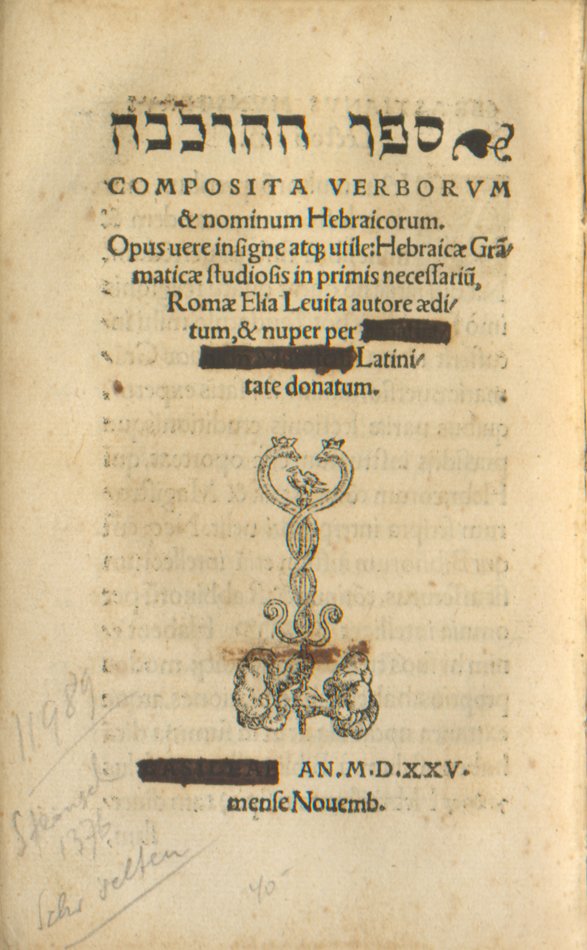

Elijah Levita (ca. 1468-1549)

Basil: [s.n.], 1525

Ludwig Rosenberger Library of Judaica

This grammatical work, the title of which means The Book of Compounds, was one of Levita’s first published works. It is concerned with the presence of foreign and compound words in the Hebrew Bible. This copy is bound with an additional work, the text of the Ten Commandments with the commentary of Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra (1089-1167). Numerous words in the text have been expurgated—crossed out by hand by a professional censor whose signature appears on the title page certifying that he has expunged all content banned by Catholic Church, including the volume’s place of publication: Protestant Basel.