University of Chicago Responds

Samuel Harper taught some of this country’s first Russian Studies courses, but it was the Cold War that gave rise to the broad research in Slavic Studies that we know today. Chauncy D. Harris, a pioneering geographer of the Soviet Union, applied to the Ford Foundation to support a Ph.D. program in Slavic at the University of Chicago in 1948, but it took the launching of Sputnik to galvanize support for such research in the United States. A Committee in Slavic Studies was formed in 1959, and a Ph.D. program was initiated in 1961. By 1964 the Committee on Slavic Area Studies included scholars in Linguistics, Political Science, Anthropology, History, Geography, Economics, Literature, Geology, and Russian Civilization.

The Russian Revolution became a contentious topic of study at the University of Chicago. Lyford Edwards’ The Natural History of Revolutions is representative of the Chicago School in sociology. Edwards, who was once dismissed from Rice Institute in Houston because of his liberal views about the Russian Revolution, argues that the American, French, and Russian revolutions were the results, rather than the causes, of social change. Following his exile from Romania, Mircea Eliade was Chair in the History of Religions at the University of Chicago Divinity School from 1958 to 1986. Eliade took confrontational positions on many fronts, and in “How Revolutions Begin” argues that ideas are turned into “the clubs and bricks of political strife” by revolution, which eventually makes them sterile.Revolutionary Soviet Cinema at the University of Chicago

Having disrupted the previously existing Russian film industry, the Revolution empowered a new generation to remake the look and feel of films. The dire lack of resources and the need to address to mass audiences pushed such filmmakers as Lev Kuleshov, Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, and Diga Vertov to develop distinctive and forceful individual styles that transformed cinema aesthetics and politicized the film experience of viewers. Soviet cinema became a means of appealing to the masses didactically and emotionally. Along with producing revolutionary films, filmmakers articulated their theories of film in theoretical texts, which competed to define the style and social goals of Soviet cinema.

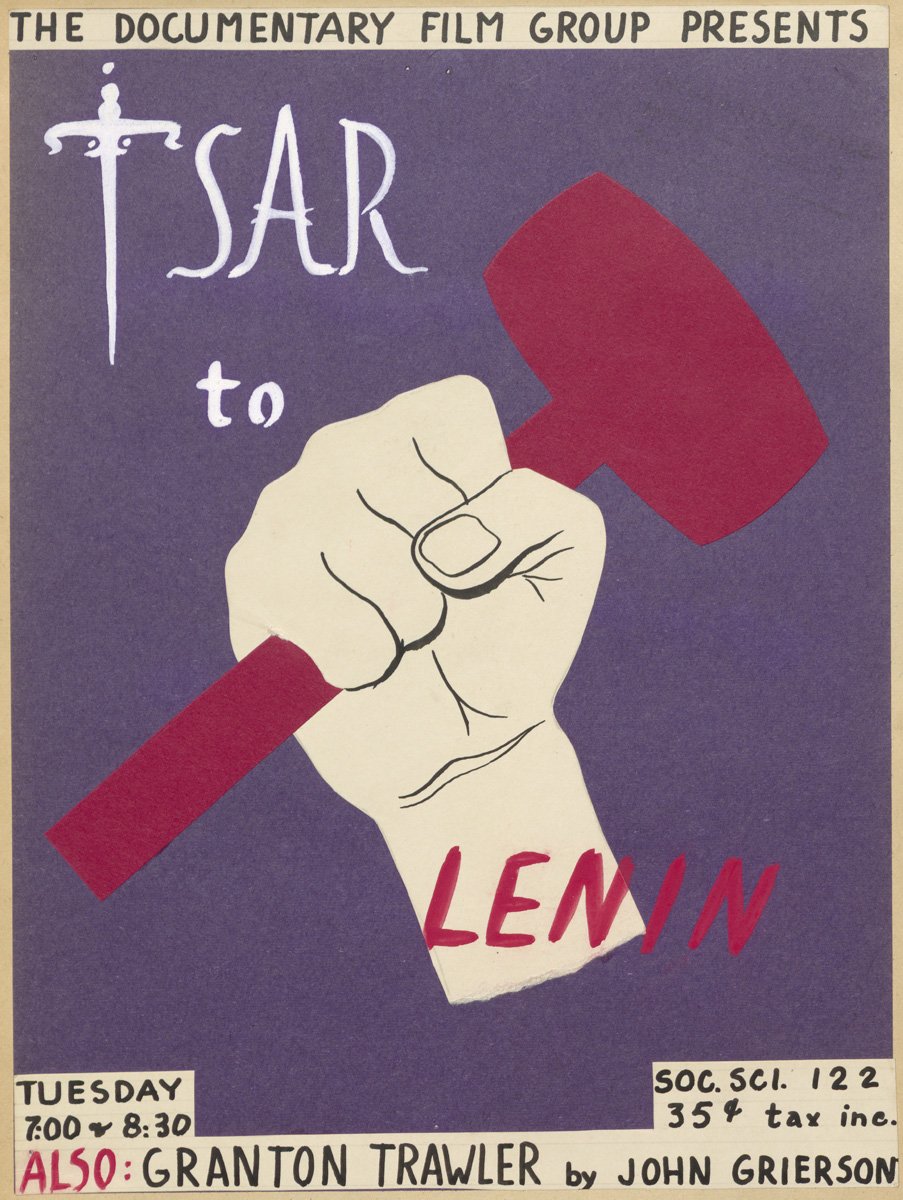

As valuable sources of knowledge about the political and social transformations in the Soviet Union, Soviet cinema almost immediately drew attention in the West from the perspectives of history, art, and political discourse. From early on the University of Chicago has been a center for the projection and study of Soviet film, especially via the Documentary Film Group (Doc Films). In 1944 a selection of Soviet films was screened by Marie Seton, one the early experts on the work of the avant-grade Soviet filmmakers. William D. Routt’s exhaustive screening notes for Eisenstein’s The General Line (Staroe i novoe, 1929) demonstrate the deep interest of cinephiles and film scholars and in the form and content of Soviet revolutionary cinema.