Blues for Mister Charlie, 1960s

If Martin Luther King, Jr. had been the civil rights movement’s leader, James Baldwin had been its prophet, like a figure from the Old Testament. Small, dark, and electrifying speaker, he functioned early in his literary journey much like Jeremiah calling out his nation’s crimes and predicting a coming conflagration.

Randall Kenan, "James Baldwin, 1924-1987: a brief biography" in Historical Guide to James Baldwin

Screen capture from Vimeo

James Baldwin and Martin Luther King Jr. at W.E.B. Du Bois' 100th Birthday Celebration, February 23, 1968

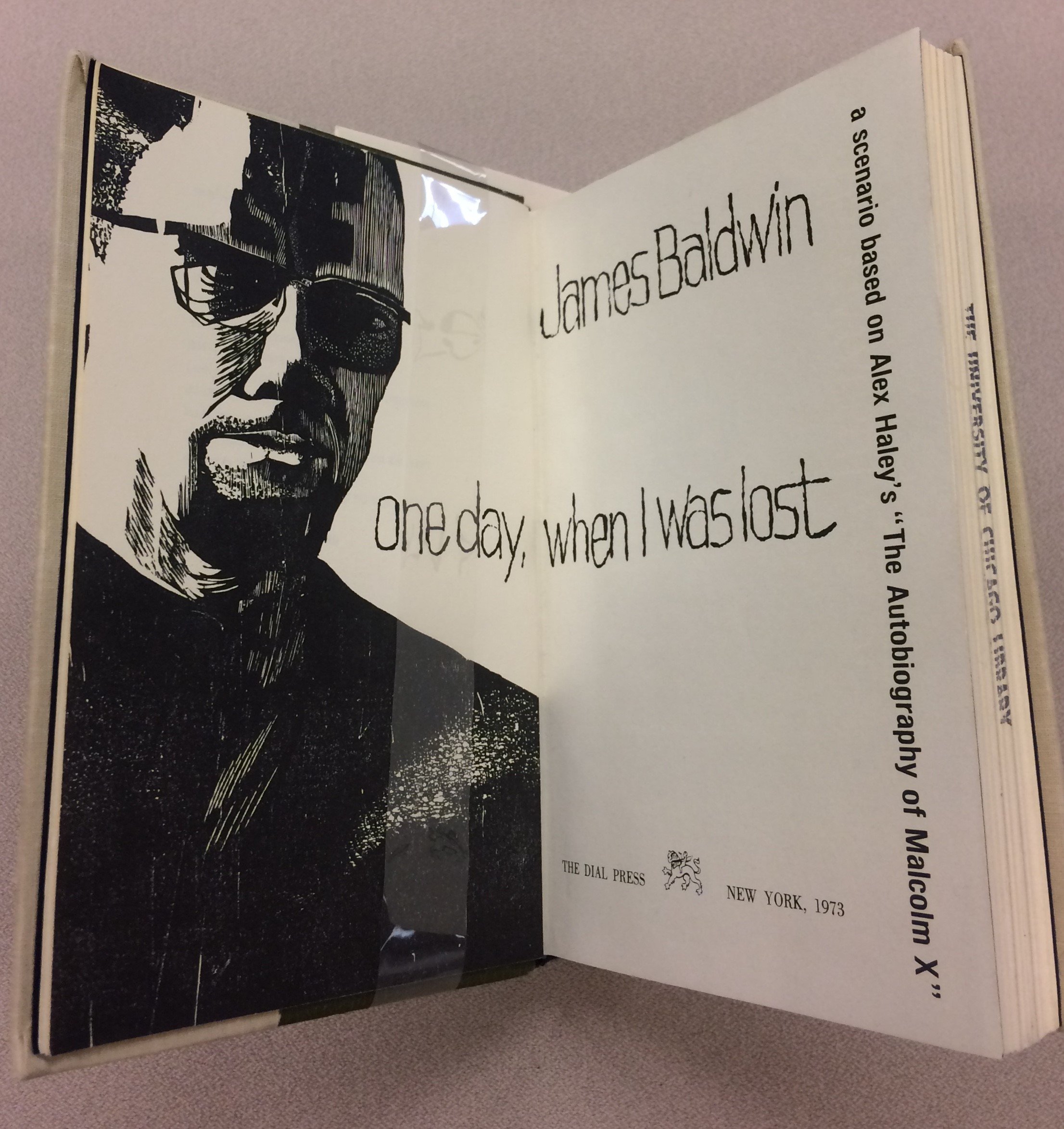

James Baldwin's first Broadway production debuted in April 1964. Blues for Mister Charlie told of the murder of a young black man in Mississippi in 1955 and was dedicated to Medgar Evers, who was assassinated in his front yard in Jackson, Mississippi on June 12, 1963. After the assassination of his friend Malcom X on Feb 21, 1965, Baldwin became increasingly bitter towards the United States. He was pressured into writing a screenplay on the life of Malcom X for Columbia Pictures. Both the producers and members of the Nation of Islam tried to influence Baldwin's work, which eventually lead to an impasse. Columbia sold the script to Warner Brothers, which was made into a documentary that was never publicly shown. Baldwin published the screenplay in 1973 as One Day, When I Was Lost, having considered the entire endeavor a failure.

I think there's a lot of love in you, Juanita. If you'll let me help you, we can give it to the world. You can't give it to the world until you find a person who can help you — love the world.

James Baldwin, Blues for Mister Charlie

Illustration: Bernard Brussel-Smith

Photo: Anne Knafl

“Baldwin’s view of equality through suffering was unlike John Locke’s liberal view of equal access to reason or free birth. If it shared Thomas Hobbes’s sobering view in Leviathan about the precariousness of human life, Baldwin saw its logical extension in compassion rather than in an excessively cold, calculating and dispassionate state. In Americans, however, Baldwin saw how the assumption of physical and emotional invulnerability encouraged moralizing apathy. Insofar as Americans were unable to accept pain, death and anguish they became monsters who were unable to feel any sort of compassion.” Alex Zamalin, African American Political Thought and American Culture.

UChicago Library copy of Blues for Mister Charlie

I know who's in prison--and I know why. I was in prison, too, and I remember it, even though I think you think I don't. All I've been trying to say is that white people in this country are what they are not because of the color of their skins--they're what they are because of this country--because they live in a racist country. I've been trying to say what I'm beginning to see--Christianity and capitalism are the two evils which have placed us where we are--in prison.

Malcom, in One Day, When I was Lost

Image by Anne Knafl

"During his trips abroad, time becomes something other than the immediate now whose punctuality Malcolm has chased as Detroit Red and NOI’s activist. In One Day, When I Was Lost, Betty Shabazz observes: 'when you left this country, you were able to see what you would never have seen if you stayed here.' His vision expands as he detaches his gaze from the immediacies that have colonized his attention...

..The living now is untimely; in death we coincide, have caught up, with our moment. That there is no such thing as an untimely death makes the setting, and resetting, of our timekeepers such an urgent task. Baldwin’s challenge is to think of an immanent, yet temporally expansive now: one where other times still infect the present moment’s singular exigency. It is in the problem’s intractability that we find something like the living core of Baldwin’s temporal ethics. "

Tuhkanen, Mikko. “Watching Time: James Baldwin and Malcolm X.” James Baldwin Review 2, no. 1 (September 1, 2016): 114.

UChicago Library copy of One Day, When I Was Lost, also available for download from Internet Archive.