James Baldwin’s work is widely recognized for its critiques of racism and heterosexual norms as well as its religious overtones and influences. His work is equally important as a contribution to American philosophy.

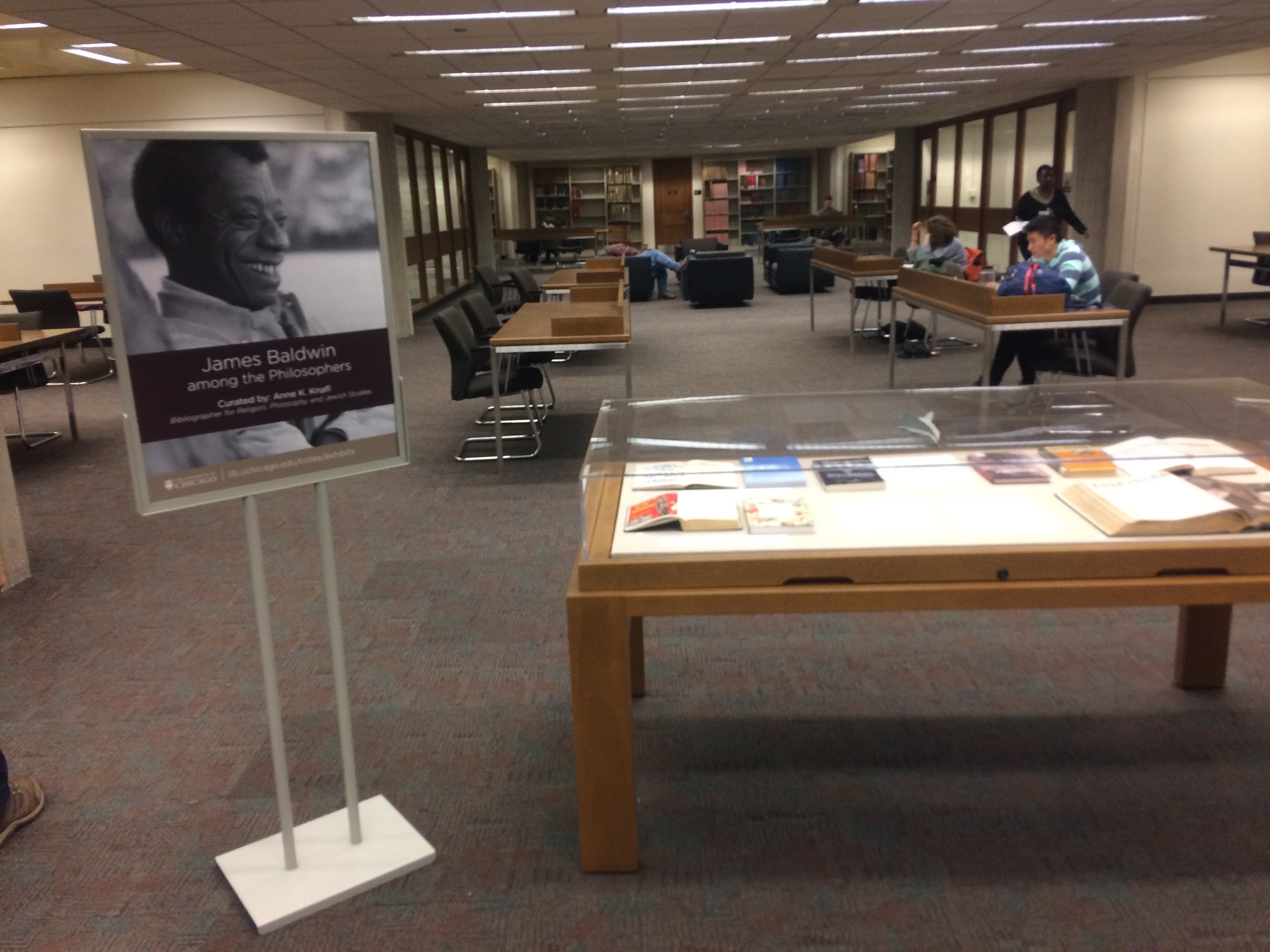

This web exhibit is based on a physical exhibit that was displayed in the Regenstein Library in 2017. The exhibit juxtaposed books and essays by James Baldwin alongside philosophical works that engage his work. The web version is a growing exhibit that incorporates new scholarship, especially published after 2017. See the Bibliography for a list of materials displayed in the physical exhibit.

Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death—ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us. But white Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

James Baldwin with Marlon Brando and Charlton Heston at Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963. Baldwin and Brando were lifelong friends, who lived together in Greenwich Village in the 1940s.

Baldwin rose to prominence in 1953, after the publication of his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical account of his childhood. By the 1960s, Baldwin had become the most recognizable African-American writer in the U.S. and the de facto spokesperson for the Civil Right Movement, a title he opposed. In 1971, traumatized by the assassinations of his friends Martin and Malcom, Baldwin moved to France, where he lived the rest of his life.

Cornel West dubbed Baldwin a “Black American Socrates” since he “infect[ed] others with the same perplexity he himself felt and grappled with: the perplexity of trying to be a decent human being and thinking person in the face of the pervasive mendacity and hypocrisy of the American empire.” Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight against Imperialism, 80.