Bound in Translations

European study of Indian languages gained momentum in the eighteenth century, when Sir William Jones (1746-1794) and other Orientalist scholars postulated the common origin of Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin, laying the foundation of Indo-European comparative philology. At the same time, European Romanticism sparked an interest in the great texts of Indian civilization, reflected here in Jones's famous 1789 translation of Kalidasa's Sanskrit drama Shakuntala.

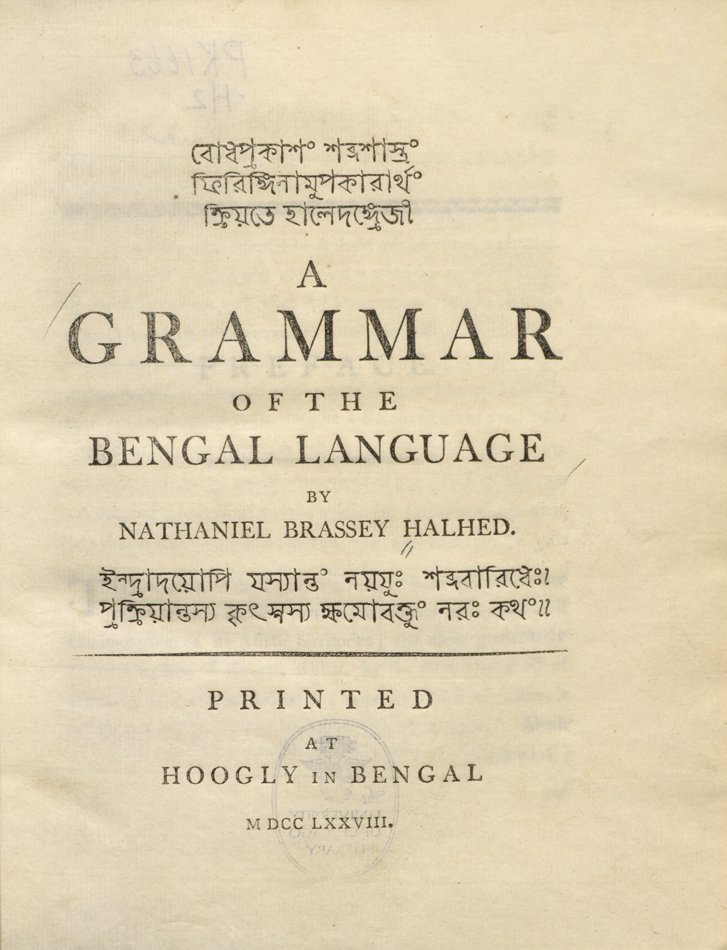

Advances in print technology aided Orientalist endeavors. The creation of movable type fonts for Indian languages enabled the production of works such as Nathaniel B. Halhed's A Grammar of the Bengal Language (1778), the first book printed with Bengali type.

From the late eighteenth century onward, the expansion of East India Company rule made it imperative to train British military and civil servants in the modern languages of South Asia. The three additional grammars shown here were among the first standard works for European learners of Urdu, Tamil, and Marathi.

Despite Orientalists' reliance on Indian linguistic expertise, the contribution of their learned assistants and interlocutors often remained unacknowledged. Recent scholarship has begun to highlight the role of indigenous intellectuals in the philological encounter. A notable example is Mohammad Ismail Khan, an Afghan scholar of Arabic, Persian, and Islamic law, who worked as Inspector of Schools. Khan produced some of the earliest handbooks on Pashto, including Khazana-i Afghani (1889), a collection of Pashto idioms with English translations.

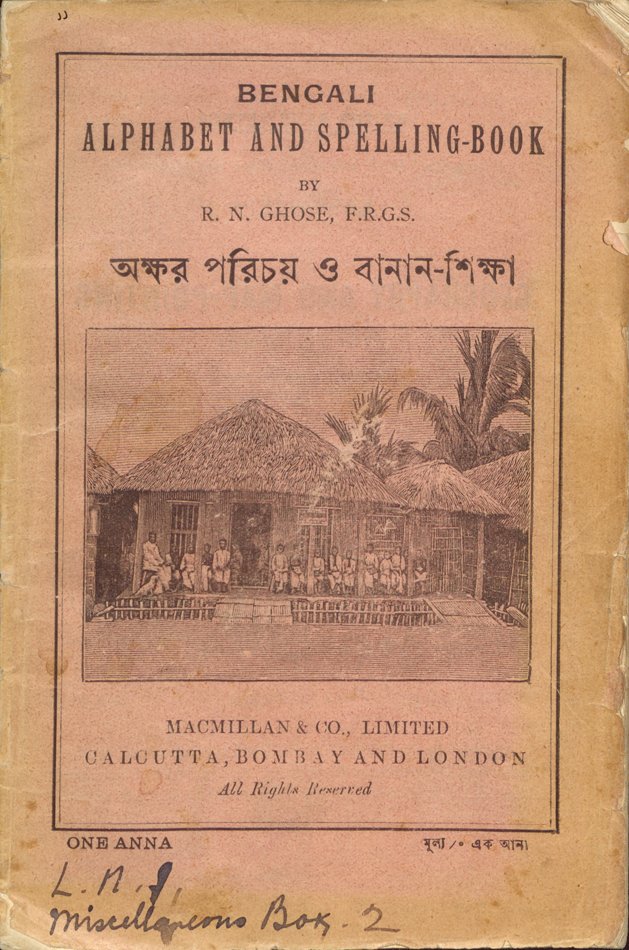

By the mid-nineteenth century, the rise of public education and literacy created a demand for primers and other linguistic aids in Indian languages. Some of the earliest schoolbooks, such as the First Reading Book in Asamese (1842) shown here, were produced by missionaries. The Bengali Alphabet and Spelling-Book (1907), published in Macmillan's 'Text Books for Schools in India' series, reflects British publishers' investment in the burgeoning subcontinental print market.

One of the most exciting finds for the exhibition's curators is this rare volume from the Library's Special Collections. Incorrectly catalogued as John Borthwick Gilchrist's The Oriental Linguist (Calcutta 1802), it is actually an incomplete copy of Gilchrist's A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language (Calcutta 1796), bound together with the first pages of the Oriental Linguist.

John Borthwick Gilchrist (1759-1841) was a prolific author, translator, and one of the foremost linguistic scholars of Persian and Urdu in British India. Born and educated in Edinburgh, Gilchrist came to India in 1782 as an assistant surgeon in the East India Company's Medical Service. He developed a keen interest in Urdu (which he termed Hindoostanee) and in 1801 was appointed head of the Hindustani Department of the newly established College of Fort William, Calcutta, a training institution for the Company's civil servants. Some of the earliest printed books in Urdu and Hindi were published under his direction. Following his return to England in 1804, Gilchrist continued to publish on Oriental languages and briefly taught at the East India Company College, Haileybury, and at University College London. He left England in 1828 and spent the rest of his life in France. He died in Paris in 1841.

The copy of Gilchrist's Grammar featured here is unique in that its interleaved pages not only contain hand-written annotations and an entire narrative text in Urdu, but also sixty drawings and paintings by one or more unidentified amateur artists who used the Grammar as a sketchbook. The uneven quality of the paintings suggests several hands. The numbered illustrations, some of which are painted over the annotations, are mostly in watercolor and start at No. 44.

The illustrations are in both European and Indian styles. While some are inspired by Indian paintings, others are drawn from observation and depict fascinating scenes from Anglo-Indian life, civilian and military, in Calcutta, Benares, and other places at the turn of the 19th century. The uniforms worn by the Company soldiers, the women's dresses, and the furniture are typical of the period.

The artists seem to have been connected to the family that is shown seated around the dining table in illustration No. 58. Some of the persons depicted in this and other paintings are identified by name, which may eventually help to establish the artists' identities.