John D. Rockefeller

The University of Chicago has long accorded John D. Rockefeller the official designation of "Founder," and that accolade may offer some historical compensation to Rockefeller's more conventional and hostile sobriquet of "robber baron." Simply put, Rockefeller's enormous contributions, totaling almost $35 million between 1892 and 1910, made possible the creation of a world-renowned research university within the short space of two decades. Although Rockefeller took great pride in the new University, he visited its campus on only two occasions—at the 1896 Quinquennial Celebration and 1901 Decennial Celebration—and each time he kept a very low profile. This modesty was in keeping with his resolute conviction that others -- especially the President and the Trustees -- needed to accept and to exercise responsibility for the new University. As Rockefeller's confidant and sometime advisor, Frederick Taylor Gates, put it to William Rainey Harper in 1892, "He would prefer in general not to take active part in the counsels of the management. He prefers to rest the whole weight of the management on the shoulders of the proper officers."

Rockefeller was a devoted and pious Baptist. His Christian

convictions pushed him to give unstintingly to his fellow human beings,

even as it tempered his giving by emphasizing the need for

self-sufficiency and good work habits among those who desired his help.

Born in Richford, New York, but raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Rockefeller

worked his way up from clerk and bookkeeper to multimillionaire and head

of the Standard Oil Company. Investments and company profits gave him

an immense personal fortune, estimated by biographer Ron Chernow to be

worth $200 million by 1897, but they did not bring him peace of mind,

nor did they bring him admiration or respect from many Americans. If

anything, his wealth became a liability; only charity, he came to

believe, could put him right with God and his fellow human beings.

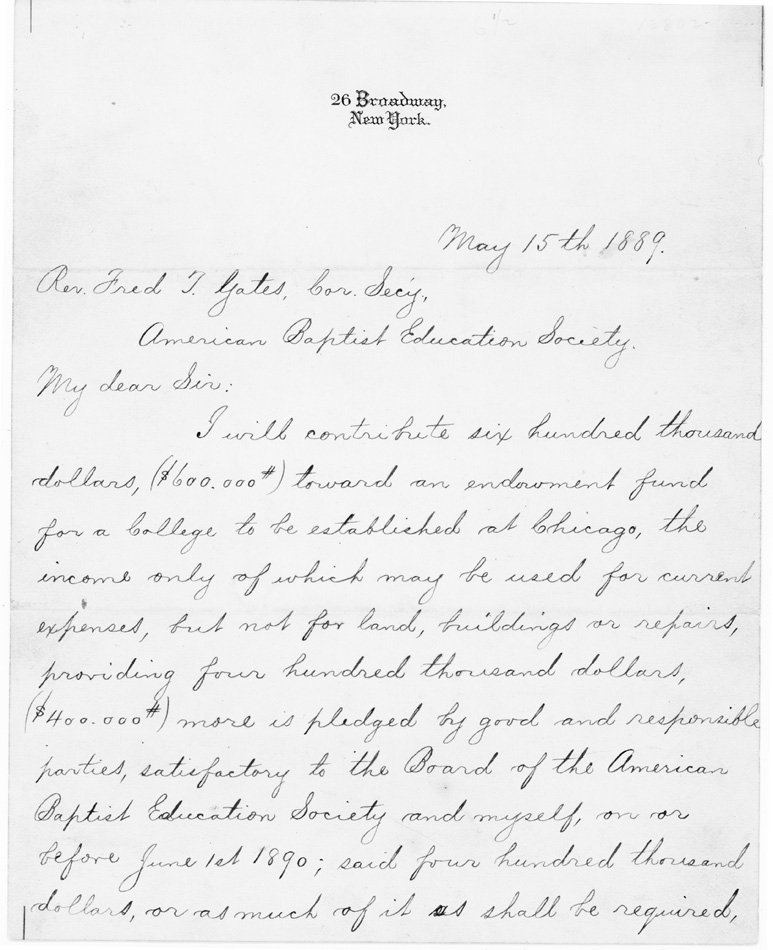

Rockefeller's initial philanthropic relations with the new

University of Chicago were forged in 1889, when he pledged $600,000 to

help launch the new university, provided that its Chicago supporters

raise an additional $400,000 within a year's time. Initially,

Rockefeller expected and wanted the University to be a liberal-arts

college, not the research university that William Rainey Harper so

strongly promoted. Moreover, he never ceased to worry that his own vast

fortune would tempt his friends and compatriots in Chicago to look to

him to support permanently the entire financial edifice of the

University. Hence, Rockefeller was especially sensitive to the need of

gaining and retaining substantial support among the members of the

Chicago civic elite. In a personal meeting with Rockefeller in April

1891, Gates had found him "troubled and depressed. He has begun to feel

that Chicago is lying down on him."

The great generosity soon displayed by early Chicago donors like

Martin Ryerson, George Walker, Sidney Kent, Marshall Field, and others

between 1891 and 1896 temporarily resolved such doubts in Rockefeller's

mind, but the issue of the proper extent of his role in supporting the

University continued to plague his relationships with Harper and the

Board of Trustees. Moreover, Rockefeller's initial worries in 1891 and

1892 over the state of the University's finances escalated over the next

decade. In his desire to attract the most distinguished research

faculty to Chicago, Harper promised salaries and departmental research

funds that the fledgling University could not afford. Soon, Rockefeller

found himself having to cover huge operating deficits, amounting to

almost 30 per cent of the annual operating budgets between 1893 and

1904, even as Harper urged him to provide additional major gifts to the

University's endowment.

After years of complaints and pleas for greater budgetary

discipline, Rockefeller and his advisers in New York seemed determined

to bring Harper under control. In late 1903 Rockefeller sent Starr J.

Murphy to Chicago on an investigative mission to undertake an

"exhaustive inquiry" into the University's operations and especially its

finances. A no-nonsense lawyer with a sharp pen and a keen eye for the

foibles of institutional budgeting, Murphy produced a long, detailed,

and insightful report in early 1904 that was generally complimentary but

also commented on Harper's almost charismatic power over his Trustees:

"The President is a man of great persuasiveness, and it is easy for him

to present to his Trustees, in a very convincing way, the importance and

necessity of the things which he desires to see accomplished. Being

subjected as they are to this pressure, and realizing the value and the

need of the various things recommended, it is not surprising that the

Trustees should be disposed to acquiesce in his plans, so far as the

resources of the institution will permit; and to be optimistic with

regard to the possibility of increasing those resources."

This situation, Murphy continued, must not be allowed to

continue, and he left no doubt who was responsible: "The existing

financial situation, and the course of financial administration for the

past few years is intolerable and must be altered. While it is desirable

and necessary that the Trustees should be men of broad intellectual

sympathy and of keen appreciation of educational needs and

possibilities, it is also necessary that they should be men of iron

resolution, capable, notwithstanding their full appreciation of these

things, of appreciating, with equal force, the limitations imposed by

financial considerations. This is where they have proved themselves

lacking, and it is in this direction that a change must be sought."

As the deficit continued to trouble Rockefeller and his advisers,

Starr Murphy submitted a second, more negative report in February 1905,

laying the blame on the officers of the University for the "constant

and alarming increase in the budget deficits." For Murphy, the

University's budget estimates were characterized by "utter

worthlessness" which offered Rockefeller "no protection whatever."

Indeed, they were "purely a matter of form, as the University

authorities do not consider themselves in any way bound by them." The

outraged reactions of Goodspeed and several other Trustees protesting

against what Goodspeed called Murphy's "offensive expressions" could not

mask the fact that Murphy had dared to express openly what others had

only been willing to ponder silently for many years.

Starr Murphy's two reports left little doubt about the origins or

the consequences of William Rainey Harper's expansionist fiscal

policies, but the University was not able to curb its habits of chronic

deficit spending until well after Harper's death in January 1906. Under

President Harry Pratt Judson's leadership, the University finally began

to exercise restraint in incurring new obligations, a change of policy

that Rockefeller certainly welcomed. In the end, nevertheless, it was

Rockefeller who had to resolve the deficit problem with several massive

additional gifts to the endowment between 1906 and 1910, concluding with

Rockefeller's Final Gift of $10 million in December 1910, his last

personal University benefaction. These gifts essentially capitalized the

structural deficit and allowed the University to bring order to its

financial affairs without compromising its scholarly reputation or

educational quality.