Howard Taylor Ricketts

Public rites marking the death of pathologist Howard T. Ricketts in 1910 commemorated an extraordinary scholarly life, lived to the full. Foreign dignitaries moved by Ricketts' campaigns against disease placed honorary ribbons on his casket. Grieving members of the scientific community named both a taxonomic family (Rickettsiaceae) and an order (Rickettsiales) after him. But the most meaningful memorial to Ricketts may have been the student research prize his family established in his honor. While Ricketts's wife and children, like most faculty families, were unable to make a large donation owing to their rather modest means, they hoped to encourage the pursuit of new knowledge that had been the focus of Ricketts' scientific life.

Howard Taylor Ricketts (1871-1910) was a native Midwesterner and a

Northwestern University medical graduate. Fascinated by the study of

disease but unwilling to restrict himself to traditional research

methods, Ricketts sometimes injected himself with pathogens as a way of

measuring their effects. This unorthodox approach, combined with his

work on blastomycosis (a fungal infection that normally affects the

skin), merited him a teaching offer in 1901 from the Department of

Pathology and Bacteriology at the University of Chicago. Before he

formally accepted the offer, Ricketts took time off to study at the

Pasteur Institute in Paris. Arriving in Chicago in 1902, he continued

his study of blastomycosis and in 1904 was appointed assistant to John

M. Dodson, the University's dean of medical students.

While at the University of Chicago, Ricketts planned an investigation of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and in 1906, with funding from the McCormick Memorial Institute, the State of Montana, the University, and the American Medical Association, he traveled to Montana to study the disease. For the next four years, Ricketts divided his life between campus-based laboratories and his research in the field. As part of his research, he contacted victims of the disease, collected and studied affected animals, and raised additional funds for his project. Not until the second year of his investigation, however, did Ricketts and his assistant J. J. Moore make a critical breakthrough by discovering that wood ticks were the primary carriers of the bacillus that caused the fever.

An outbreak of typhus in Mexico City caught Ricketts's attention, and taking advantage of a leave of absence from the University of Chicago and relying on the principles he had established in his Montana research, Ricketts went to Mexico in 1909 and plunged into his study of typhus. There he discovered that typhus closely resembled spotted fever, leading him to argue that insects spread both diseases. Unknown to Ricketts, this same conclusion had been reached by the French surgeon Jules Henri Nicolle, who identified lice as the culprits. Ricketts's final stint of research was cut short by a critical illness. Just days after isolating the microorganism he contended was the cause of typhus, Ricketts died on May 5, 1910, most likely from an infected insect's bite.

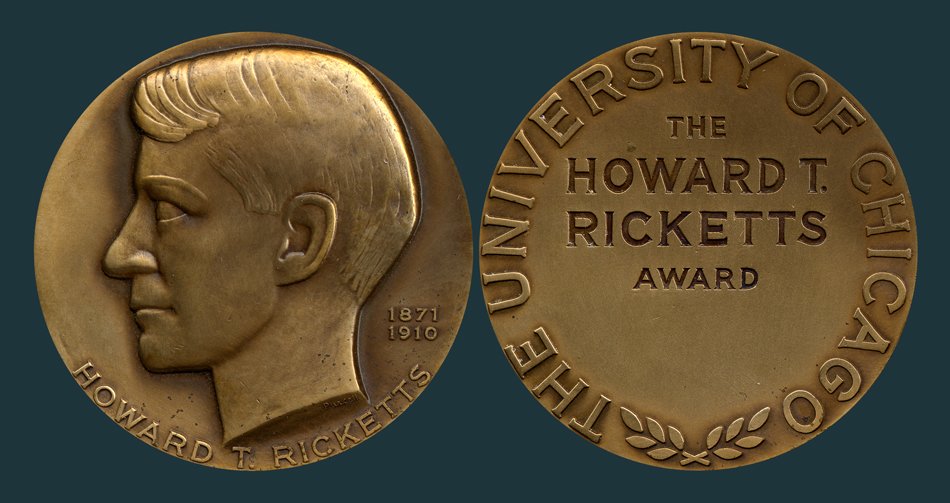

As a memorial to her husband, Myra Tubbs Ricketts in 1912 donated $5,000 to the University. She stipulated that the income from the endowment was to go to providing an annual prize—the Howard Taylor Ricketts Prize—for "the student presenting the best results of research in Pathology or Bacteriology." Others who were moved to memorialize Ricketts raised money to build a laboratory in his honor for the Department of Pathology, Hygiene, and Bacteriology. Named the Ricketts Laboratory, the building was erected in 1914 and stood on Ellis Avenue until its site was claimed more than seventy years later by the Kersten Physics Teaching Center and the gate to the Science Quadrangles.