Rare Chinese texts spark collaboration

The United States is home to many important pre-modern Chinese texts, from the only surviving copy of some volumes of a 15th-century Encyclopedia, the Yongledadian, to the Sequel to Yuanxiang qijiu shiji, an unpublished manuscript of a poetry collection from the Qing dynasty held at the University of Chicago Library. The University of Chicago’s collection of Chinese rare books alone comprises some 10,000 volumes.

Yet not enough is known about how scholars use these collections, the preservation needs of the materials, or what preservation efforts are under way across the country. According to Yuan Zhou, curator of the Library’s East Asian Collection, scholars from China and the West need more ways to share expertise and to learn from each other.

So this May, Zhou and Prof. Edward Shaughnessy organized a conference at the University of Chicago’s Mansueto Library to provide a forum for scholars, collection curators, and preservation specialists from China and the West to collaborate and share their knowledge of pre-modern Chinese materials. “Texting China—Composition, Transmission, Preservation of Pre-modern Chinese Textual Materials” also provided a rare opportunity for scholars of Chinese texts to present alongside library curators and preservation specialists from leading institutions in China, Taiwan, the United States, Canada, and Europe.

The Mansueto Library was an especially fitting choice of location for the conference, according to Library Director Judith Nadler. The new library, with its cutting-edge preservation facilities, Nadler said, “is both a symbol and the realization of the commitment to preservation and access to global resources that support scholarship worldwide.”

The event was held in honor of Tsuen-Hsien (T.H.) Tsien, Professor Emeritus in East Asian Languages and Civilizations, who made what Nadler described as a “remarkable contribution to the study and preservation of China’s literary heritage” during his lengthy career at UChicago. The event was a reunion of sorts for Tsien and several of his students, who now head the East Asia collections at top universities throughout the United States and returned to Chicago to celebrate the work of their former teacher.

“A needed collaboration”

“I went into this conference thinking there were major differences in the things that needed to be done with Chinese books and with Western books,” says Shaughnessy, the Lorraine J. and Herlee G. Creel Distinguished Service Professor in Early Chinese Studies. He was encouraged to discover that the knowledge gap was significantly smaller than he initially thought.

The fundamentals of preserving and conserving Western and Chinese materials are very similar, although early Chinese materials often use types of paper and ink, and binding methods that are less familiar to conservators trained in the West. “Even though the science is the same, the format is different,” explains Shaughnessy.

Preservation of early texts is vital to the work of scholars like Shaughnessy, who studies the cultural and literary history of the early Zhou period. He is currently at work on a survey of recently excavated examples of the Yi Jing (Book of Changes) an ancient Chinese text used for divination.

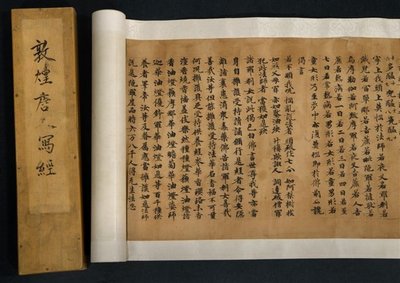

During the conference, all participants reaped the benefits of their counterparts’ expertise. For example, the Library holds a Dunhuang manuscript scroll that contains three fragments of Buddhist sutras, thought to date back to the 9th century. An expert from the National Library of China, who has studied numerous similar pieces at his own institution, examined the manuscript and suggested the piece was even older than it was initially appraised by the Library. Judging from the paper and calligraphy, he dated the piece to the seventh century.

In addition, Zhou and a delegation of experts from the National Library of China visited the Field Museum to examine a Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) rubbing of the Lanting Xu, a collection of poetry inscribed by master calligrapher Wang Xishi. Based on his expertise with early royal families and collectors’ seals, Zhang Zhiqing, deputy director of the National Library of China, was able to verify the authenticity of the rubbing, and proposed that it may be the oldest existing copy of the Lanting Xu.

This kind of interchange is exactly what the conference was designed to promote. “Everyone agreed it was a needed collaboration,” Zhou says. In fact, the conference was the first of its kind in the United States that brought together an international assemblage of scholars who use the entire span of pre-modern Chinese written materials in their research with librarians who care for these materials to discuss their making, dissemination, and preservation.

“Texting China” also came in the midst of significant efforts to broaden the study of China at the University of Chicago. In addition to the creation of the University’s Center in Beijing and the Confucius Institute, two leading experts on China, historian Kenneth Pomeranz and comparative literature scholar Haun Saussy, have joined the faculty as University Professors.

“A legendary figure”

The conference provided an opportunity to honor Tsien, whom Zhou described as a “legendary figure” in his field. Tsien, 102, came to the University in 1947 and went on to become the curator of the East Asian collection. He also taught at UChicago’s former library school and in East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

In addition to his work at Chicago, Tsien is known for his heroic efforts to protect China’s literary heritage in World War II. During the Japanese occupation of China, Tsien risked his life to help smuggle more than 100 wooden crates of rare books from the National Library of China to the United States.

The fruits of Tsien’s effort to protect Chinese rare books were on display at the conference, as scholars from UChicago and elsewhere discussed their work on pre-modern Chinese texts. Donald Harper, the Centennial Professor of Chinese Studies, discussed his study of the provenance of the Chu Silk Manuscript, now held by the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. Yuming He, Assistant Professor in East Asian Languages and Civilizations, presented her work on global consciousness in the Ming Period.

Only a beginning

During this two-and-half-day conference, 23 presentations were delivered, followed by two roundtable panel discussions. The scholars and librarians from China and the West exchanged their research findings in studying pre-modern Chinese texts, shared their experience in preserving and conserving these materials, and discussed issues of mutual concern.

In an era when many are forecasting the death of the physical book, Shaughnessy found it especially meaningful to have scholars present alongside the librarians who care for the materials they study. “As the significance of the digital age has really dawned on scholars of all stripes, I think it’s impressed itself upon them that we really need to know [about] the media that carries this information,” he says.

Zhou says he was heartened by the collaboration that took place at the event. In this regard, “this conference is only a beginning,” Zhou says. He and Shaughnessy hope to eventually develop an exchange program with the National Library of China that would allow preservation specialists in the East and West to work together. Other conference participants proposed assessing the preservation needs of pre-modern Chinese texts, creating an international digital registry of these materials, undertaking more collaborative digitization projects, assessing educational needs and developing a curriculum to meet them, and fundraising to support preservation efforts.

“These materials need to be preserved,” Zhou says. “The conference brought people a higher awareness of such need, and [it] shows that colleagues from the West and China are very willing to work together and pursue this shared goal.”